A Sermon by Rev. John E. Gibbons

Delivered on Sunday, October 25, 2015

at The First Parish in Bedford, Massachusetts

From 1980 to 1990, I was the minister of the Unitarian Congregation of Mendon and Uxbridge, Massachusetts. These are small towns in southern Worcester County, near the Rhode Island line. Uxbridge had been a mill town; Mendon had farms. I can be nostalgic about those years: the rural pace was slower, the people, many of whom had lived there for generations, were good and kind and familiar.

My office was in the Mendon church. Most days, at noon, I walked down the street to Mendon center, a simple crossroads with adjacent post office, police station, a minuscule library, Danny’s Variety Store (“If we don’t have it; you probably don’t need it”), and the Lowell Insurance Agency. Usually, I got my lunch at Danny’s and then I’d take it to an old oak chair in the corner of my parishioner David Lowell’s office – which was filled with assorted antiques, a hobby about which he was more passionate than his profession as an insurance agent. Noontimes we’d be joined by the postmaster, the furniture-refinisher, other townspeople and parishioners, and over hot dogs and beans we’d solve all the world’s problems.

At lunchtime on Friday, December 9, 1988, David was behind his desk, Gary (the furniture-refinisher) sat nearby, and I was in my corner chair next to the window by the sidewalk outside. At 12:45 p.m. there erupted a volley of gunshots. The three of us dove to the floor.

When we got up we saw that a Pontiac station wagon, heading north, had slammed into a utility pole perhaps 50 feet from us. Some yards to the south I saw a standing police officer lower his shotgun. The vehicle had passed by him and the officer had fired several shots through the rear window of the station wagon, striking the driver in the head and shoulders, killing him. David recalls the officer then opening the driver’s door, grabbing the young black man by the hair, and pulling his body onto the road where it lay crumpled.

David, Gary, and I must have surveyed the scene for a while but then, it seems that after lunch we all went back to work. Surely we talked about what had happened but life went on for us, seemingly unaffected. Two days later I preached a sermon titled “Letting Go” – about holiday expectations, I think – with not a mention of Friday’s horror – and I must have taken my own advice for I largely let go of my memory of that day.

Oh, it was in the newspapers. The dead black man was 23-year old Marc Murray. He and two white teenage accomplices had been caught breaking into a house in the nearby town of Blackstone. They had a microwave and a VCR. Confronted by Blackstone police, the two white kids fled on foot. Marc Murray got into their stolen car, backed into a police cruiser, and made his escape toward Mendon. In the confusion, an officer either slipped or was bumped to the ground, then with his service revolver managed to fire several shots into the car, none of which hit Murray.

On their police radios, two white police officers in Mendon – Matthew Mantoni and Ernest Horn – heard “officer down” and “shots fired.” They grabbed two shotguns and waited for the fleeing Murray to drive the six miles from Blackstone to Mendon.

Just before the town center, standing in the road, Horn tried to stop Murray but Murray kept on going. Then, in the center of town, 50 feet from where I sat, Murray passed Mantoni and it was then that Mantoni fired three rounds from his shotgun. Seized in evidence was the Atlanta Falcons baseball cap Murray wore, holes shot through its back.

Murray was unarmed.

Mantoni and Horn were praised by their superiors but suspended pending the DA’s inquest six months later. They were exonerated and returned to work where they remain on duty today.

News reports further noted that Mantoni’s grandfather, a former Mendon police chief, was – in 1950 – the last Mendon officer to be killed in the line of duty when he responded to a disturbance at a local bar.

And so we have another shooting death of an unarmed black man by a white police officer; and, likewise, we recall that police, too, risk their lives.

For a long time, I put all of this in the back of my mind.

And then came Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis and Eric Garner and Tamir Rice and Walter Scott and Eric Harris and Freddie Gray and Sandra Bland and so many more.

It was last winter, 27 years after the events I had witnessed, that I realized I wanted to remember what had happened. I wanted to know more. I realized that, in light of current events, I was haunted by my memories.

Whether repressed or simply forgotten, I couldn’t remember much. Not the name of the victim, not even the year. David and Gary couldn’t remember much either.

I wanted to at least find the news stories that appeared in the local papers but, without a date, I couldn’t begin.

I contacted funeral directors I had known when I was there but they had no knowledge.

Thinking that a phone call to the Mendon police might put them on the defensive, I contacted a reference librarian in nearby Milford. She emailed the Mendon police chief who replied that he’d get back to her. He never did.

In July, I decided to call the chief myself and I left messages on his voicemail. In August, David and I even visited the station. All we wanted was the date. No one remembered anything.

Then in August, amidst his antiques and bric-a-brac, David discovered a yellowed news clipping. We had the date: December 9, 1988. The clipping also revealed that the other Mendon officer with a shotgun that day was Ernest Horn. Today, Ernest Horn is Mendon’s chief of police, the one who stonewalled and never responded to our inquiries.

I needed to know more. With the help of reference librarians in Milford and Woonsocket, I got copies of all the news reports. At the end of the summer I visited the Milford Town Clerk and got a copy of Marc Murray’s death certificate. It says he was buried in Swan Point Cemetery in Providence. David went looking for his grave but Marc Murray wasn’t there.

The death certificate says his mother was Jane L. Murray of Greenville, Rhode Island. She is no longer there. I searched the Internet. I made phone calls and sent emails to a lot of Jane Murray’s, none of whom was Marc’s mother. And then a cluster of leads led me to Jane Murray Robertson in Raleigh, North Carolina. I left phone messages and emailed. I told her I wanted to respect her privacy, I didn’t want to cause trouble, but that I had witnessed her son’s death and that no one should die so horribly. I wanted to understand what I had witnessed, know more about Marc and, however belatedly, I wanted to offer my condolences.

On August 13 I got an email from Marc’s mother and I opened it in tears. She was overwhelmed and surprised and grateful. She said she wanted to talk with me but she needed time. A couple of weeks later, she called me here and we talked for more than an hour. She had prayed for the courage to talk. Her pastor told her, “God repels all fears.”

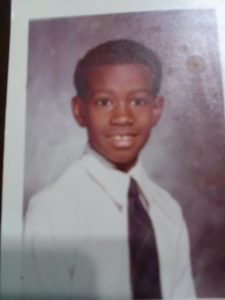

She told me about Marc and all that happened. Marc was born when she was 15, the eldest of three children. Marc was the “craziest kid you’d ever hope to meet” – in the good sense. He was happy and he smiled and, especially when he wanted something, he called his mother, “Mommy.” He’d graduated from Pawtucket High School. He worked in a pizza shop in Providence. He was good to his mother and grandmother. Yes, he’d gotten in some trouble; he liked to steal cars; he was not violent.

December 8, the day before he died, was his birthday and Jane went to her grandmother’s house in Providence where Marc was living but Marc didn’t come home. Jane wanted to give him a hundred dollars. If only he had come home, she regrets, maybe the next day would have been different.

Police did not notify her until 3am on December 10. She identified him by a photograph. She never saw his body. She was glad that I had been there, that someone who cared about her son, had been there when he died.

Marc was cremated. “Where is he buried?” I asked. “He’s right here,” she answered, “His ashes are next to me, on my table.”

She attended the inquest after the shooting, the only black woman in the courtroom. Another witness from Mendon testified, even closer than I had been. From his front porch he saw Marc’s car coming and he saw it pass. “It was an entirely unjustified shooting,” he testified.

Jane and her two other children have endured much since Marc’s death. They’ve had counseling for PTSD. They’ve been depressed and angry and sad. Her husband, Marc’s stepfather, was killed in a construction accident. Jane’s been a substitute school teacher and she had a lingerie business. Now she has lupus but she also makes jewelry, and she goes to an integrated church in Chapel Hill where they’re working at becoming more multicultural and multiracial.

A couple of Sundays ago, her white pastor asked the congregation “What happened on September 15, 1963? I don’t want to see any black hands (the pastor said); I want to see white hands!” All the black parishioners knew that that was the date of the Birmingham church bombing when four little black girls were killed. Jane’s pastor said, “We’ll be making some progress when white folks know that date as well as black folks.”

Jane and I have spoken twice more. She seems to enjoy talking about Marc. We’ll talk again. Sometime I even may visit her in Raleigh!

Well, this has been quite a journey for me and it’s not over. Even in shorthand, let me tell you some of the places I’ve been:

I’ve made public records requests to the Mendon police and to the Worcester DA – for police logs, autopsy reports, witness statements, the transcript of the inquest. Chief Horn responded to me, saying Mendon has nothing. The DA has given me the bare bones of the State Police account, but I’ll be requesting more. I’ve learned that Massachusetts has some of the weakest public records laws in the nation.

I’ve pondered what might have been going on for Marc Murray. He was by no means an innocent but I don’t think he deserved to die. At the scene of the housebreak, when shots were first fired, some might think that a reasonable person would give up and do whatever the police wanted. But if I were a 23-year-old black guy, I might reasonably say, “These people are ready to kill me. They’re trying to kill me. I gotta get outta here.”

Police work is, of course, hazardous; but we ought never forget that we, the people, give police their guns and we give them the right to appropriately employ deadly force. In an interview following another police shooting he was not involved in, Chief Horn recalled the events of 1988 that I witnessed and said, “It’s something you live with for the rest of your life. I can remember the day the individual was killed. You don’t forget it. It’s like it happened yesterday. I don’t remember his name, but I remember every second of the event.”

This is the chief who would not provide even the date of the Murray shooting. And if an officer must use deadly force, I’d really want them to remember the name of the one they killed.

This is a journey that has taken me to our Bedford police chief who reviewed our own rules on deadly force. And, whether in Mendon or in Bedford, let’s hope that policing has changed in the last 30 years. Our Bedford chief referred me to the 1985 Supreme Court case, Tennessee v. Garner, which ruled that in pursuing a fleeing suspect, an officer may not use deadly force to prevent escape unless “the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others.”

I cannot understand how the Murray case rose to that standard of threat. Mantoni and Horn claimed their lives were threatened, but Murray’s car had passed when Mantoni shot him in the back of the head.

This is a journey that, in late August, took me to Oak Bluffs on the Vineyard where Harvard professor Charles Ogletree (who has spoken from this pulpit) hosts an annual conference on race. This year’s theme was “Black and Blue: Policing the Color Line.” Present were attorneys, academics, politicians, community leaders, human rights and Black Lives Matter activists. The sole white panelist was Lisa Thurau who used to live in Bedford and attend this church, and who now directs a program that trains both police and youth to more helpfully interact with one another.

I learned a lot, including the rather astounding fact that organized policing in America has its institutional origins in the early 19th century slave patrols in South Carolina that captured escaped slaves. Policing in America started with the purpose of catching black people. Go look it up! There is a unique history to the relationship of black people and the police, a history that is known in the bones of black people and mostly unknown to white people.

Police are the first incendiary point of contact with every institution that defends the racist status quo.

As a white person, I was in the minority at that Vineyard conference. Sitting in the high school auditorium, a middle-aged black woman sat down next to me. I introduced myself as a minister of the First Parish in Bedford and her eyes widened. She introduced herself as Priscilla Douglas who grew up in Bedford. The Douglases were the first black family in Bedford in the 20th century. She was in the first graduating class of Bedford High School and she was the state Secretary of Consumer Affairs in the cabinet of Governor Bill Weld. Actually, I recalled meeting her before and for many years her brother Billy was my auto mechanic.

On a break, I asked Priscilla Douglas what her interactions with police have been. She recalled a Halloween in Bedford – in the 60’s perhaps – when four teenagers, her brother Deacon among them, were picked up by the police for some pranks. The three white kids were held until their parents posted bail. Her brother was held without bail, then sent to the Billerica House of Correction. Circumstances spiraled and, in circumstances I do not know, Deacon was killed.

Every African-American knows these stories.

Bedford’s African-American Terry Parker remembers a time in the 70’s when his father visited the Bedford police station and behind the chief’s desk was a town map with push-pins in every address where black people lived in Bedford.

This is a history known in the bones of all black people, nearly unknown to whites.

My journey with the memory of Marc Murray has introduced me to Roxbury journalist and community activist Jamarhl Crawford who maintains a website called Blackstonian. On it he maintains a gallery of black people in Massachusetts killed by police. On it he will add the name of Marc Murray. Eager to talk with me, Crawford said, “Every black person knows someone who has been killed. This isn’t news to us! What we need are white allies whose eyes have been opened.”

This journey has led me to a review of DA inquests into the uses of deadly force. Very often, as in the case of Marc Murray, DA’s have rubber-stamped police justification of deadly force. As soon as a chief who may have no first-hand knowledge whatsoever says, “Yes, my officer acted properly,” it is typical for everyone else to fall into line with what may be the truth or may be a cover-up. Let me know if you want footnotes because I can back up my claims!

This journey has taken me to a conversation last week with Ron Hampton, Washington D.C. police officer and past president of the National Black Police Association. At great personal risk, Hampton has advocated changes in police work, recalling the not-too-distant past when black and white police officers were prohibited to patrol together in the same cruiser. Still today in many cities a majority of the police force live outside the city and are altogether unfamiliar with day-to-day life in the neighborhoods they patrol.

Hampton says that, inasmuch as “Black Lives Matter” calls for police to know the communities they serve, it is a pro-police slogan because better relationships between people and police mean more safety for people and more safety for police.

Hampton says that reforms are good, cameras are good (if the tapes are publicly available) but even more fundamental is for us to recall that the police serve the people, not the other way around. In too many parts of our country, the police are a virtually unregulated unsupervised military force, insulated by regressive fraternal orders of police who defend the status quo. Hampton recommends, by the way, the new film Peace Officer, set in Utah with not a single black person in sight but which documents the increasingly militarized state of American police.

I know that some would claim that there’s been a “Ferguson effect,” that crime has risen as police are reluctant to engage lest a video go viral. Such is the not-unexpected speculation of those who resist change, who defend the status quo.

I am significantly influenced by Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book, Between the World and Me, which I commend to you. In the form of a letter to his 15-year old son, Coates writes with a physical/visceral/embodied awareness of race that reflects a new guttural tone in the racial justice movement, an awareness as real as the clenched fist of the Mendon police officer who grabbed Marc Murray by the hair and threw his dead body to the pavement.

It seems not coincidental that Coates’ letter to his son pivots on the news that his close college friend Prince Jones, unarmed and unprovoked, was shot dead by police. Exactly as was claimed by those who shot Marc Murray, those who shot Prince Jones claimed he tried to run them over. “The officer,” Coates says, “given maximum power, bore minimum responsibility. He was charged with nothing. He was punished by no one. He was returned to work.”

I’ll end with extended quotations. Coates speaks, first of all, of the gulf between white and black perceptions of America. Recalling his upbringing, Coates recalls,

”Somewhere out there beyond the firmament, past the asteroid belt, there were other worlds where children did not regularly fear for their bodies. I knew this because there was a large television resting in my living room. In the evenings I would sit before this television bearing witness to the dispatches from this other world. There were little white boys with complete collections of football cards, and their only want was a popular girlfriend and their only worry was poison oak. That other world was suburban and endless, organized around pot roasts, blueberry pies, fireworks, ice cream sundaes, immaculate bathrooms, and small toy trucks that were loosed in wooded backyards with streams and glens. Comparing these dispatches with the facts of my native world, I came to understand that my country was a galaxy, and this galaxy stretched from the pandemonium of West Baltimore to the happy hunting grounds of Mr. Belevedere….I knew that my portion of the American galaxy, whose bodies were enslaved by a tenacious gravity, was black and that the other, liberated portion was not.”

Waking up white, it is vital to know that our experience of the American galaxy is vastly different than experienced by so many others.

Coates continues,

“At this moment the phrase ‘police reform’ has come into vogue, and the actions of our publicly appointed guardians have attracted attention presidential and pedestrian. You may have heard the talk of diversity, sensitivity training, and body cameras. These are fine and applicable, but they understate the task and allow the citizens of this country to pretend that there is real distance between their own attitudes and those of the ones appointed to protect them. The truth is that the police reflect America in all of its will and fear, and whatever we might make of this country’s criminal justice policy, it cannot be said that it was imposed by a repressive minority. The abuses that have followed from these policies – the sprawling carceral state, the random detention of black people, the torture of suspects – are the product of democratic will. And so to challenge the police is to challenge the American people who send them into the ghettos armed with the same self-generated fears that compelled the people who think they are white to flee the cities and into the Dream. The problem with the police is not that they are fascist pigs but that our country is ruled by majoritarian pigs.”

These are hard words; hard truths.

Finally, Coates acknowledges the difficulty of the task before us:

“The mettle which it takes to look away from the horror of our prison system, from police forces transformed into armies, from the long war against the black body, is not forged overnight. This is the practiced habit of jabbing out one’s eyes and forgetting the habit of hands. To acknowledge these horrors means turning away from the brightly rendered versions of your country as it has always declared itself and turning toward something murkier and unknown. It is still too difficult for most Americans to do this. But that is your work. It must be, if only to preserve the sanctity of your mind.”

I have not yet completed my journey to remember and to redeem the life, death and meaning of Marc William Murray. I sense that it is not to recover some nostalgic or idealistic sense of the American Dream but rather to pursue an American future, as yet murkier and unknown.

It is religious work to reveal the larger truths of our lives, to unpack our memory, if only to reveal a future as yet murky and unknown. If only to preserve the sanctity of my mind, I hope to continue this work.

I welcome your companionship on this journey.